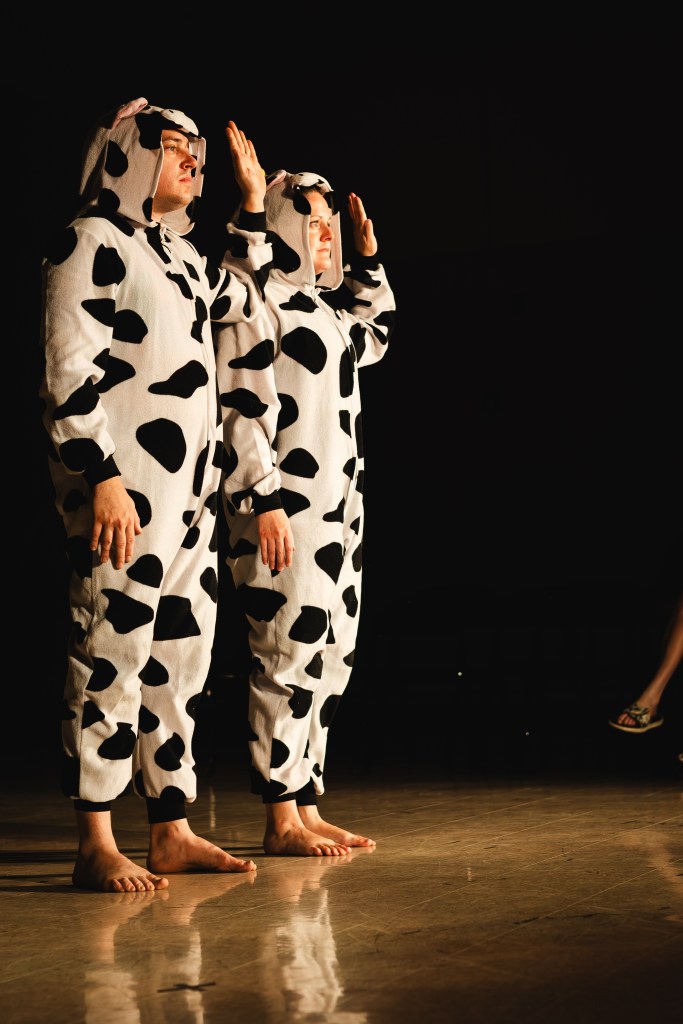

The following writing is a response to the July 18th, 2025 performance of Cloven conceived and performed by Jacob Mark Henss and Betsy Brandt (St. Louis, MO/ Champaign, IL) The performance was presented by the BorderLight Festival on unceded Erie territory (aka Cleveland, OH) at the Cleveland State University Theatre Arts building.

“I am a farmer,” Jacob says convincingly.

“You are?” Betsy inquires. Jacob shows her the notes. “Jacob is a farmer,” she confirms for us.

“You are the cow,” he continues.

“Wait what?” she interrupts, clearly unhappy with the comparison. She confirms the stage direction, “I am a cow.”

I squirm at the gender implications.

After letting the audience sit in the discomfort of Jacob-Man-Farmer, Betsy-Woman-Cow for long enough, Jacob suggests they exchange roles to perform a full AI demonstration. Betsy becomes the be-gloved farmer, and Jacob, poised precariously on two stools, receives the artificial insemination. This queerness persists in their performance relationship throughout. An ass is slapped, a body is tossed. The power never settles with either of them.

Betsy reminds me, as she’s greeting her son and his girlfriend in a sweaty post-performance haze: “There was a wonderful man at the Urbana performance who we all knew who really didn’t want to give the syringe back…”

Perhaps this is an unconscious acknowledgment of where the power really is in the room of performance — with those who watch.

This is the magic of multi-year tours for dancers and choreographers: the ability to reflect on the impact your performance work has through time. These tours are rarer and rarer as the economics of dance continue to tighten. Funded here, in part, by the BorderLight Festival in Cleveland, OH, Cloven is able to be experienced in a pre- and post-Tr**p 2.0 context.

This administration is hurting all of us, in ways that are probably too deep to calculate right now. That’s not new, though, the systems around us were built to exploit us. Manufacture convenience to distract from the fact that slavery never ended and our communities are vanishing. Our tax dollars are funding international wars instead of community health. They take away our free time, our attention, our families, our health, our livelihoods, our will to live. We watch (and dutifully pay our monthly subscriptions) as our representative democracy continues to represent a smaller, and wealthier, sect of the populous.

It feels bleak, and dear reader, if you’re reading this and it doesn’t feel bleak. I ask you to open your heart to hear the pain in the world around you. It’s not new, but it’s persistent.

What happens to a farmer when they stop being a farmer?

I’ve known Jacob since 2019 when we danced together at an intensive. Betsy and I met around the same time through my tenure as an MFA student at the University of Illinois. This is the first project I’ve seen them do together, though. I was able to document their performance in Urbana, IL last March, and I’m struck by new resonances in this July 2025 moment.

I remember when Betsy took me to get my first ever plate of ceviche.

“No squid please,” she entreated the waiter.

“I don’t eat cephalopods. I can’t eat anything with that much intelligence.”

She speaks matter-of-factly, often, about things that could be considered controversial. It’s one of the things I admire most about her. She doesn’t bourré around when it comes to her convictions. It’s empowering. I took this credence on, going forward. I always ordered the fish ceviche. I never got fried calamari for the table (although, to be honest they always freaked me out).

“These chicken were definitely GMO,” my brother-in-law quips as he brings dinner to the table. Suddenly, I’m deboning a chicken leg for my niece, and I feel every muscle that I pull off this avian bone twitch in my leg in empathy. Glute max, med, min, hamstrings…

What happens to an animal when it stops being an animal?

Jacob proclaims triumphantly at the beginning “This is a piece about cows.” However, in its many cow-print trappings (many of which he designed and constructed), it’s rarely about just that. From the accurately graphic description of the process of impregnating milk cows to a cheeky anti-Artificial Intelligence rant that Betsy launches, text operates as subtext throughout. At one point, “former faculty member” Betsy auctions her “former student” Jacob off to the highest academic bidder as his CV (“auction materials”) scrolls in projection behind.

The scene is based in reality, with a script that fluctuates, but I was struck to see that Jacob’s CV wasn’t up-to-date. It’s probably more complicated to update a projection cue than to improvise a quick line change, but knowing Jacob, there was a lot of work missing from the last year! Jacob shared with me that he was recently interviewing about a piece that he is starting, while rehearsing Cloven, and negotiating jobs to support his artistic work. This is the reality of making art in America. It’s frequently not a career, even when it’s a full-time job.

“Let the bidding start at $55,000 a year plus benefits and research support.”

——

I remember feeling an ick about this moment of the performance in 2024: the proximity to addressing the history and present of slavery in the agriculture industry. This country’s entire economic infrastructure was built by stolen human beings on stolen lands and neither wound has ever been repaired. In some ways, this moment serves to make that supremely clear. Here is this farm-raised blue-eyed boy. He has not escaped the system of underpaid, overworked labor. What makes you think you have? For an audience of mostly white-presenting theatre-goers. Is that enough?

The thing they don’t tell you about economics is that it only applies when the population you’re studying is too big to just ask. It turns individuals, humans, people into collective behaviors. Our representative democracy was created when the fucking town crier just called everyone down to the town center to elect a representative. Maybe it’s time for something new?

I find myself walking through the Lake County Fair in the northeast suburbs of Cleveland. I buy a strawberry lemonade boba from a 20-something. I pass families, farmers, immigrants, goths, queers, cows, horses, mules.

Where is our representative? Does he represent all of us?

———————

There’s an exhibit where live chicks are hatching throughout the fair. “We’ve gotta go home for dinner!” My sister says, holding my newborn nephew. “What’s for dinner?” my niece responds as she watches a black and grey chick peck through its shell.

“Grilled…chicken.” my sister responds.

———————

What happens to an elbow-length plastic glove used for a cattle’s rectal probe when it has outlived its intended purpose? You use it in performance.

———————

“Jacob and his cows” would be another appropriate title for this piece. It’s a featured scrawl from a slideshow that closes the work–filled with photos of photographs of younger Jacob with his calves and heifers. The phrase is more than that, though. Jacob has a unique knack for creating an ecology for his work that people buy into. It’s one of the things that makes his SpaceStation residency in St. Louis so successful, and it lives in the Cloven ecosystem of works. With student iterations at several universities and a small midwestern tour, Jacob’s herd continues to grow.

There’s a familiar lore among the children of immigrants. I’m not quite sure where it originates, but every child of immigrants is familiar with it. Our parents moved here to make enough money to send us to college to get good jobs as doctors, lawyers, engineers. Then we’d have enough money for our kids to grow up to become artists, poets, dreamers.

But what happens to the artists, poets, dreamers and dancers when they’re raised in the cutthroat kitchen with the doctors, lawyers, and engineers. We’re all funneled through this system through elite institutions we can’t afford, to work for elite institutions we can’t afford to leave, because they subsidize our health insurance. We’re ground up like meat, fed unsubsidized antidepressants, and told to take on a third job.

We’re writing the grant for the next project while we tour a previous and prepare to premiere a third.

What happens to an immigrant person when they stop being a person?

It’s incredible to watch dancers in their craft. I saw a recent interview of Cynthia Erivo saying singing is so powerful because the voice can’t lie. I hope she wouldn’t mind me saying, I think it’s the body more generally that doesn’t lie. These two dancers cantilevered in space, becoming one mass of flesh and fabric, don’t hide their trainings. Feet are pointed, and knees are straight. More interesting to me, though, is the secret algorithms bubbling under the surface of the performance.

Betsy reaches to turn on the battery-powered leaf blower. It doesn’t take. Panic. Fuck, I think. I want it to be perfect. I want this sensuous lap dance with a landscaping tool to be slathered in the pristine sheen of a music video. Before I can finish the thought, Betsy—taking her time—has locked the blower in place and is receiving the full DIY Beyoncé experience. You can tell it’s not always pleasant, but she is committed. I should have waited. I should have trusted her to get where she needed to be. I should have trusted the performance to go where it was supposed to go. I was so worried about…what? This is the magic of live performance. It’s never quite the same, but it’s always right.

Maybe we expect live performance to be as spectacular as the multi-million dollar movies and glossy social media we’re used to seeing. That’s not the work that it’s doing though. There’s a little more than 20 of us in this room watching Betsy and Jacob graze in an imaginary meadow. We trust them, for 45 minutes, to take us where we need to go. Even in the violence, or the chaos, or the “contemporary dance” of it all. We know that Betsy and Jacob (and husbands Josh and Mike) are underneath all of that, taking care of each other, and taking care of us.

Does it require generations of farming forefathers to interpret a cow chewing cud this accurately?

Probably not, but it doesn’t hurt.

Betsy asked me to consider something that she’s been thinking about dramaturgically, “What is the place of something this ridiculous at the end of times?”

I like the question, but I’m going to do the proper neurodivergent thing and share a question that it reminds me of.

What is the place of performance?

Okay we can keep “at the end of times” if you want.

I’ve been asking myself this question a lot recently. I think a lot of us have. What good does my art do when people are being rounded up by masked federal agents? I don’t know what my answer is, but I do know.

Cloven reminds us that it’s important to be uncomfortable every once in a while.

———————

Sometimes it’s uncomfortable to be visibly trans in those spaces. The facial hair that makes me cringe when I look in the mirror is a shield of privilege.

My dogs wear blue collars because blue is my favorite color.

Sometimes it’s uncomfortable to be visibly trans in comfortable spaces. My sister serves “sibling” and all the lipstick, nail polish, long hair, and sibilance I have cannot save us from the jarring volley of “brothers” and “he’s” that are returned.

“Oh what a cutie, how old is he?”

“She’s 3, I think? She was abandoned in a park.”

“OH MY GOSH SHE, I’M SO SORRY.”

Sometimes it’s uncomfortable to be wrong.

———————

Betsy hurls deli slices at Jacob’s sweaty torso with the ferocity of an Olympic javelin throw. She brushes past me and the eddies of wind that follow her clear plastic raincoat smell like meat. When she walks away, I smell sweat. Jacob is inches away from me splayed out green on a linoleum mat. Betsy looks at Jacob with the tenderness of a mother cow. She places the remaining meat over his chest like a shrine. Then, together, they stand and collect the meat on a wooden tray before passing a slice to each audience member, folded like a flower.

Betsy remarks that she’s surprised everyone accepted their token. “Sometimes people refuse, which I totally get.”

But by that point, we were with them. We were together for the ride. We wouldn’t disrespect the performers’ work. We couldn’t disrespect these animals that died to give their flesh to this sacrificial rite. We watched everything til now.

So, we each sit and watch Jacob move through the memory of some dancing we saw to Kylie Minogue earlier. Holding our stinky meat flower and watching “Jacob and his cows.”

more by Elliot Reza

Leave a comment